At the end of February 2025, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) warned that the country would experience above average temperatures in March across most regions with an above normal number of heatwave days. This forecast came on the back of what had been reported as the hottest February in India since 1901.

It did not take long for the forecasted extreme heat to develop with temperatures in some regions reaching 45°C by mid March and being described as being one of the earliest heatwaves in the history of the broader region. Higher than normal minimum temperatures were also experienced with 28.1°C in Trivandrum, the capital of the southern Indian state of Kerala. Also early heatwaves in Maharashtra and Goa combined with high humidity, amplified the potential for heat stress.

In Eastern India, Boudh recorded India’s highest temperature on March 16 at 43.6°C and by late March the IMD issued further heatwave alerts with Delhi experiencing a temperature of 40°C on 26 March, 6.3°C above normal. I

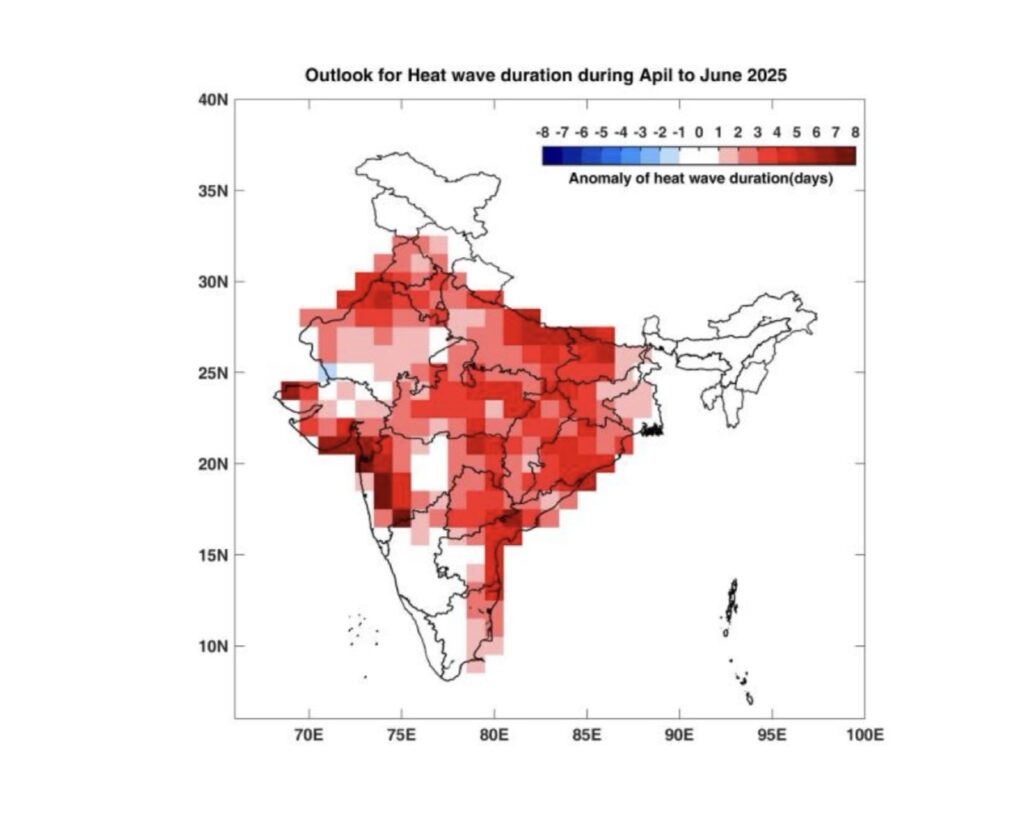

In their seasonal outlook for the hot weather season covering the period from April to June published at the end of March, the IMD again forecasted above-normal maximum temperatures over most parts of the country with the exception of west peninsular India, isolated regions of east-central and east India experiencing normal maximum temperatures. Above norm minimum temperatures were expected across most of the country. The summary also highlighted the likelihood of above-normal number of heatwave days occurring over most parts of the north and east peninsula, central and east India along with the plains of the northwest. With potentially 10–12 heatwave days expected compared to the usual 5–6.

Notable temperatures in April included the Rajasthan cities of Barmer recording 45.6°C and Jaipur 43°C, while in Rajkot in Gujarat State , a temperature of 44.2°C was recorded.

Now in early May there is little sign of the exceptional temperatures abating with every indication that temperatures will continue to be higher than normal through the month.

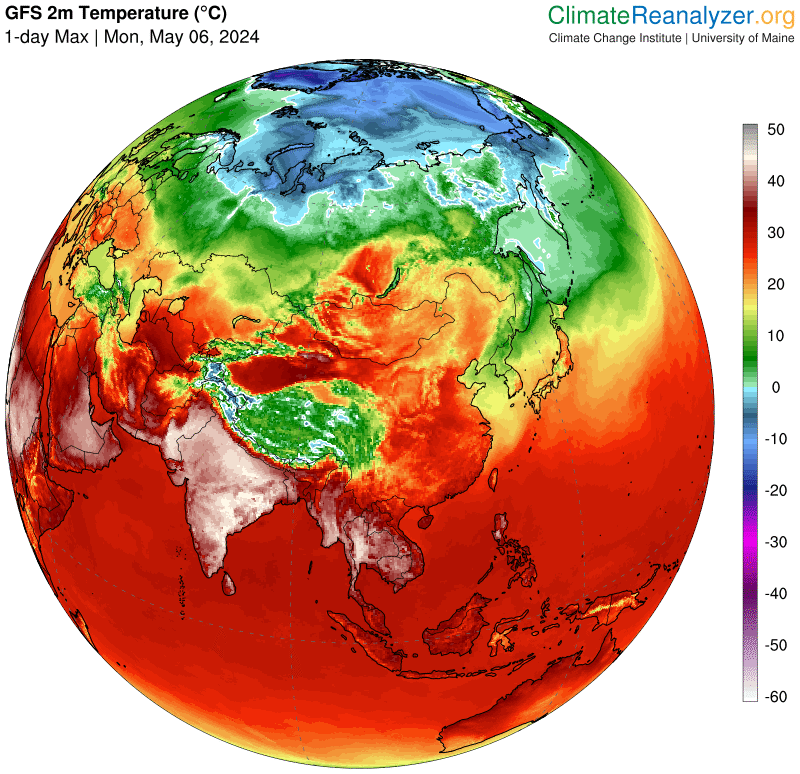

The map visualization of one day maximum air temperature for Monday 6 May from Climate Reanalyzer shows the intensification of the extreme heat in India for the majority of the country at temperatures above 45°C.

In addition to an attribution of the extreme conditions being associated with climate change, forecasters have explained that fewer and weaker western disturbances (moisture-laden winds from the Mediterranean) in 2025 have allowed hot, dry winds from Pakistan and Afghanistan to raise temperatures in northern India.

Mumbai, India’s second-largest city with 21.7 million residents, provides a good example of how various factors drive rising temperatures in increasingly urbanized areas with pronounced urban heat islands. This year, reduced snowfall in Jammu and Kashmir has weakened western winds, causing higher minimum temperatures in Mumbai. Additionally, intensified construction during the monsoon, combined with calmer winter winds, has failed to clear dust particles, leaving them suspended and worsening air quality.

The Indian press has extensively covered the above-normal temperatures and intense heatwaves across the country, emphasizing their early onset of the higher temperatures, widespread impact, and severe consequences for health, agriculture, and the economy. The debate increasingly focuses on the sustainability of living in such conditions for an extended period of time with the press framing the heat as a “new normal.” The situation being exacerbated by the density of population and the lack of access to cooling facilities.

An increase of heatstroke and heat-related illnesses is inevitable with the current situation creating moderate health risks for infants, the elderly, and those with chronic diseases. The “Heat Watch 2024” report, titled Struck by Heat: A News Analysis of Heat Stroke Deaths in India in 2024, indicated that between March and June, 733 deaths were reported across 17 states in India as a result of heatstroke Various sources have subsequently suggested that the report underreported the deaths associated with the heat through the period of time ithat was reported.

Individuals such as outdoor workers, fishermen, and slum dwellers in coastal cities face increased risk due to inadequate access to cooling. A 2022 Lancet study showed a 55% increase in heat-related deaths in India from 2000–2004 to 2017–2021, particularly in coastal areas affected by humid heat.

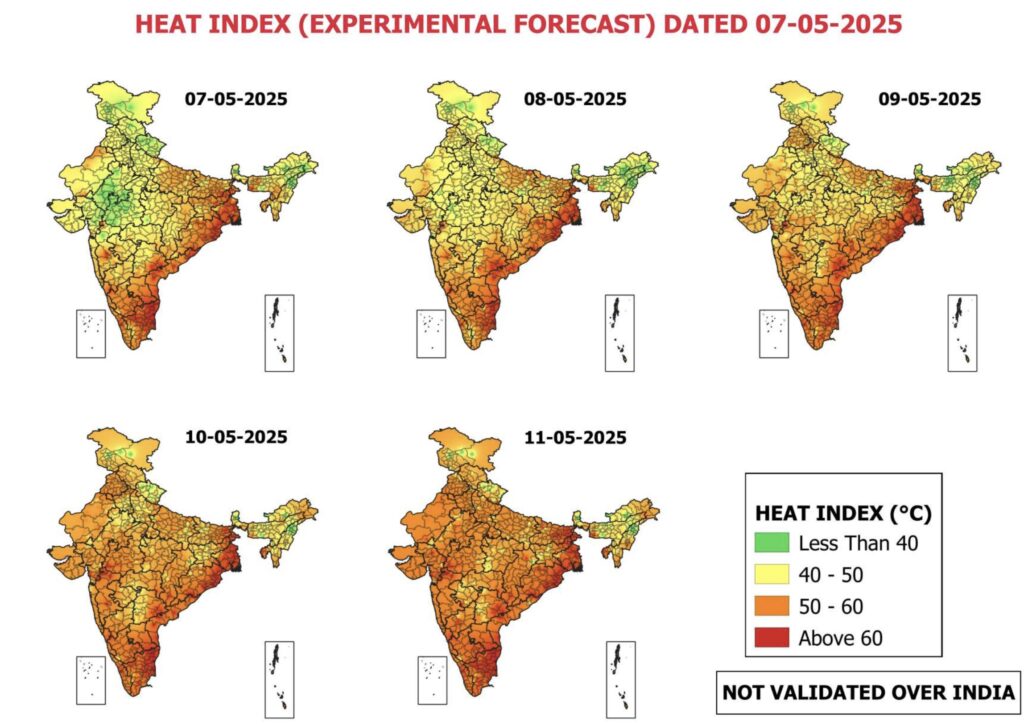

Two measures that could enhance understanding and provide a more detailed perspective on the effects of elevated temperatures across various regions of the country are the Heat Index and Wet Bulb Temperature. Heat Index data which is now available from the IMD focuses on comfort and perceived heat stress — how hot it feels to the human body when air temperature and relative humidity are combined. Expressed in °F or °C, it’s designed to communicate heat stress risks for public health and safety and to issue heat advisories.

Categories include “Caution” (27-32°C), “Extreme Caution” (33-41°C) “Danger” (42-51°C), or “Extreme Danger” (52°C and above). A temperature of 38.7°C with 70% humidity in Mumbai in March 2025 yielded a Heat Index of 50.6°C (Danger).

The Heat Index forecast dated 7 May 2025 provides a good insight to the particular cities and states potentially most at risk from the above normal temperatures. The south east state of Tamil Nadu and the city of Chennai having the highest heat index temperatures and being very much in the most dangerous category. By the 11 May the heat index temperature rises across the country but still with the greatest risks found in the eastern coastal states.

The Wet Bulb Temperature (WBT) directly measures the thermodynamic limit of human cooling via sweat evaporation, making it a better indicator of survivability. Expressed in °C, it is always lower than or equal to the dry bulb temperature due to evaporative cooling. Wet Bulb Temperature (WBT) is an essential but often underutilized indicator for assessing extreme heat stress, especially in humid regions like coastal India.

Coastal areas lose substantial outdoor work hours due to high WBTs. A McKinsey report from 2020 estimated India loses 21% annually, increasing to 24% by 2030 and 30% by 2050. Heatwaves in 2025 have already impacted fishing, construction, and tourism in Mumbai and Goa.

Key WBT thresholds have been established with WBTs between 30–31°C considered being dangerous for prolonged outdoor activity, particularly for vulnerable populations, while WBTs between 31.5–35°C highlighting conditions that can become potentially lethal within hours, even for healthy individuals, as the body loses its ability to thermoregulate effectively.

In mid-April 2025, Solapur in Maharashtra state, recorded a temperature of 40°C with 53% humidity, producing a calculated wet bulb temperature of approximately 31.54°C. This placed it near the threshold of lethality typically associated with coastal regions although being an inland state.

The risks are even more pronounced in coastal cities like Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata, where relative humidity frequently reaches 70–95%. In such conditions, WBTs can climb to 31–35°C even at relatively moderate air temperatures between 34–38°C. While the Heat Index may indicate high discomfort (e.g., values of 50°C), it does not adequately represent the point at which heat becomes unsurvivable, something WBT captures more precisely.

The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) continues to emphasize dry-bulb temperature, which has the potential to underreport life-threatening conditions in humid environments. For instance, in April 2025, media and public attention focused on a 44°C reading in dry Jaipur, while less attention was paid to potentially more dangerous wet bulb conditions along the coast.

This underrepresentation of WBT in public communication is due in part to the complexity of measurement and a general lack of awareness. However, as climate change increases both temperatures and humidity, the recognition and forecasting of dangerous “wet bulb events” will be vital to protecting public health, particularly in densely populated, poorly ventilated urban areas along the coast.