A team from Queen Mary’s University encountered exceptional conditions in February of this year on a fieldwork visit to Svalbard

The team found higher than normal temperatures, widespread snowmelt and blooming vegetation. Now a commentary of the research undertaken has been published in Nature Communications titled ‘Svalbard winter warming is reaching melting point‘ with the team revealing the dramatic shift in the Arctic winter.

For many Svalbard is very much at the front line of the climate crisis with warming trends six to seven times the global average rate. It is reported that the winter period is experiencing the highest rates of warming with winter temperatures over Svalbard rising at nearly twice the annual average. The commentary highlights that winter warming in the Arctic is no longer an exception but a recurring feature of a profoundly modified climate system, challenging the long-held assumption of a reliably frozen Arctic winter.

Also of significance are the changes in annual precipitation, particularly in west Svalbard where increases of 3–4 % per decade have been found, of which a greater proportion is falling as rain. The projection is for rain to become the dominant form of precipitation in the Arctic by the end of this century.

The team were based in Ny-Ålesund, the world’s northernmost permanent settlement, situated in north-west Svalbard and approximately 1,200 km from the North Pole with the focus on studying glacial and terrestrial microbial communities and their role in carbon and other elemental cycles during the dark, frozen, winter period.

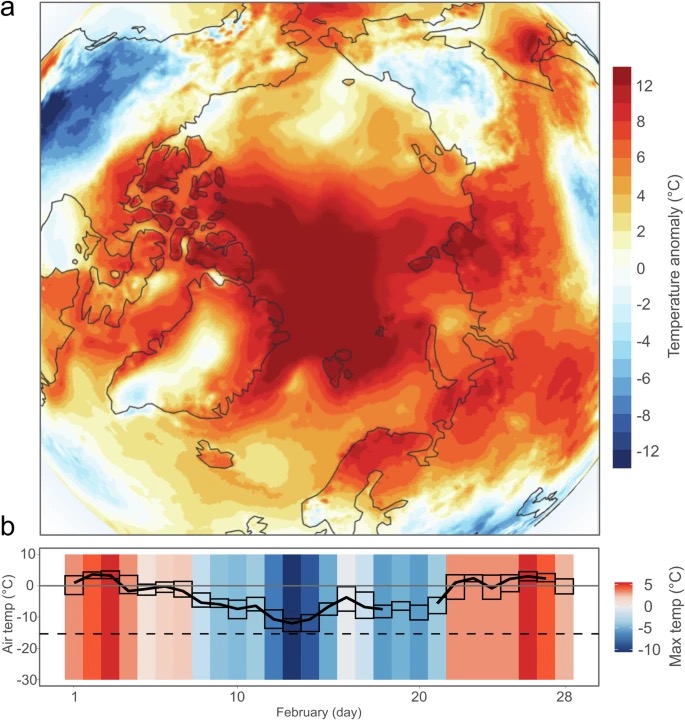

This year, Arctic winter air temperatures were among the warmest ever recorded with the the air temperature average for Ny-Ålesund for February 2025 at -3.3 °C and considerably higher than the 1961-2001 average for this time of year of -15 °C. Air temperatures persistently above 0 °C were encountered in February.

Source: Svalbard winter warming is reaching melting point – Nature Communications 2025

a Surface air temperature anomaly for February 2025 over the Arctic region relative to the February average for the period 1991–2020. Data source: ERA5, obtained from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). b Daily air temperatures for February 2025 from Ny-Ålesund observation station, Svalbard, elevation 8 m, established in July 1974. The solid black line is the daily average. The black boxes represent the minimum and maximum temperatures recorded. The horizontal dashed black line represents the average air temperatures for Longyearbyen, Svalbard, for the month of February between 1959–2001, estimated from the instrumental Svalbard Airport series. Background stripes are colored according to the daily maximum temperature.

Dr James Bradley lead scientist for the fieldwork commented “Standing in pools of water at the snout of the glacier, or on bare, green tundra, was shocking and surreal. The thick snowpack covering the landscape vanished within days. The gear I packed felt like a relic from another climate.”

Laura Molares Moncayo, a Ph.D. student at Queen Mary and the Natural History Museum and a co-author on the study, added, “The goal of our fieldwork campaign was to study freshly fallen snow. But over a two-week period, we were only able to collect fresh snow once, as most of the precipitation fell as rain. This lack of snowfall in the middle of winter undermines our ability to establish a representative baseline for frozen-season processes.”

This firsthand experience of the team from Queen Mary’s corroborates long-standing projections about Arctic amplification, but it also underscores the alarming speed at which these changes are taking hold. Meltwater pooling above frozen ground, forming vast temporary lakes was observed along with glacier-fed streams and rivers that would usually remain frozen until springtime. Snow cover on the tundra was reduced to zero across large areas with the reduced snow cover leading to greater exposure of the bare ground surface. Vegetation emerged through the melting snow and ice, displaying green hues typically associated with spring and summer.

The implications of rapid winter changes for the Arctic ecosystem are far-reaching. Winter warming events can disrupt everything from microbial carbon cycling to the survival of Arctic wildlife. These events may also create a feedback loop, accelerating permafrost thaw, microbial carbon degradation, and the release of greenhouse gases across the Arctic. A ‘New Arctic’ is developing that will require monitoring on a larger scale to enable a significant increase in data and ultimately an improved understanding of the dynamic nature of the changes.

“Climate policy must catch up to the reality that the Arctic is changing much faster than expected, and winter is at the heart of that shift,” states Dr. James Bradley.